In Tate St Ives

- Artist

- Bob Law 1934–2004

- Medium

- Lead

- Dimensions

- Object: 440 × 295 × 30 mm, 4.4 kg

- Collection

- Tate

- Acquisition

- Purchased 2006

- Reference

- T12178

Summary

This sculptural work in lead takes the two-dimensional form of a squat obelisk or simple, triangle-roofed house, upon which a poem by the artist has been stamped in slightly irregularly spaced and off-kilter, sans-serif capital letters. A hole has been drilled through the apex at the very top of the panel, to the left of which the place name ‘TWICKENHAM’ is set on an uneven diagonal in small capitals; perhaps serving as a geographical annotation to the poem’s writing, in correlation to Law’s habit of assiduously dating both his drawings and paintings. To increase legibility, the surface of the work is dusted with a coat of high-contrasting white flour for presentation. The work’s title is also the first line of the poem, the text of which reads in its entirety:

IS A MIND A PRISON

OF CELLS

WHO IS

MISTER CRABTREE

THE MAN WITH THE HACKSAW

WHO INDEED

IS MISTER CELL

THE AMINO ACID MAN

UP THE SPIRAL STAIRCASE

THROUGH YOUR GRANDMOTHERS BEDROOM

TO A DISTANT LIGHT

BEYOND THE RED SHIFT

TO A DIVISION OF

DIVISIONS

REGIMENTS OF DIVISIONS

MARCH THROUGH REFLECTIONS

OF A MIRRORLESS MIRROR

WOULD YOU LIKE TO BE

DADDY LONGLEGS

ON THE GREATEST

SPACESHIP EARTH ODYSSEY

WE ARE ALL SUSPECTS

BEING SUSSED OUT

Law made a small number of concrete poetry works in lead in the 1980s and a handful in the period from the late 1960s to 1970s, during which the work in Tate’s collection was also executed. The layout of text on these panels (in Fibonacci spiral, intersecting cross-hatch, or standard lines) varies as much as their overall form, whether augmented obelisk or rectangle, while a few include engraved outlines of dogs but no other figurative markings.

For this work, Law literally inscribes each letter of his thought-poem onto the surface of the readymade unit of durable metal to produce an object imbued with cultural, natural and mystical forces. And the text itself expresses a mixture of biological, astrological and banal imagery together with intimations of a solipsistic paranoia; the ‘reflections / of a mirrorless mirror’ might contain an allusion to the artist’s Black Paintings, for instance No. 62 (Black/Blue/Violet/Blue) 1967 (Tate T02092), which were to be experienced by viewers as thoroughly meditative surfaces. In this sense, the lead-poems significantly and singularly elucidate the diverse themes infusing Law’s aesthetically minimal artworks, even concretely establishing their conceptual grounds. With regard to their quasi-literary format, Law had been exposed to beatnik culture in St Ives as well as at Bob Cobbing’s Better Books in Charing Cross Road, where the American poet Allen Ginsburg read in the 1970s.

In 1960 Law relocated to the Richmond district of London from Cornwall. Like many artists at the time he also worked as a builder’s carpenter and salvaged the lead roofing sheets from which the ground material for Is the Mind a Prison is composed from a building site in the city. The artist David Batchelor has described Law’s lead works as embodying a physical relationship to the world and to representation. A preoccupation with the physical and material dimensions of perception is at the heart of Law’s oeuvre, which intersects minimalism, conceptual art, and abstract painting informed by landscape, Zen mysticism and carpentry. As the art historian Anna Lovatt has remarked: ‘[Law’s] work indicates an alternative tradition of art and thought in which numerical series and blank surfaces are a means of grappling with metaphysical questions’ (Anna Lovatt, ‘Bob Law: Drawing Degree Zero’ in Batchelor, Bond, Lovatt 2009, p.21). It is this particular, ‘alternative’ openness in Law’s sculptural works too, investing minimal materials with narrative power, which can be cited as an influence on later artists including Barry Flanagan, Tony Cragg and the New British Sculpture of the 1980s.

The practice of art was an ongoing intellectual project for Law, who considered art to be ‘the result of thousands of years of thinking how to think’ (Law quoted in Batchelor, Bond, Lovatt 2009, p.25). This work from Tate’s collection reflects the paradox of this understanding as much as the impossible task of expression, which the artist forever struggles to overcome via plastic means: ‘I have, or I think I have, my perfect work in my mind’s eye’ (Law quoted in Whitechapel Art Gallery 1978, p.14).

Further reading

Bob Law: Paintings and Drawings, exhibition catalogue, Whitechapel Art Gallery, London 1978.

David Batchelor, Anthony Bond, Anna Lovatt and others, Bob Law: A Retrospective, Ridinghouse, London 2009, reproduced p.122.

Kari Rittenbach

February 2012

Does this text contain inaccurate information or language that you feel we should improve or change? We would like to hear from you.

Display caption

Law’s concrete poem, the first line of which serves as the work’s title, has been inscribed into a squat obelisk made of salvaged lead roofing sheet from his work as a builder’s joiner. Law has used individual sans serif letter stamps, resulting in both a printed and hand-made finish, and for display the work is dusted with flour to highlight the script. A preoccupation with the physical and material dimensions of perception is key to Law’s work, which intersects minimalism, conceptual art and abstract painting informed by landscape, Zen Buddhism and carpentry.

Gallery label, September 2016

Does this text contain inaccurate information or language that you feel we should improve or change? We would like to hear from you.

Explore

- abstraction(8,615)

-

- non-representational(6,161)

- education, science and learning(1,416)

-

- psychology(176)

You might like

-

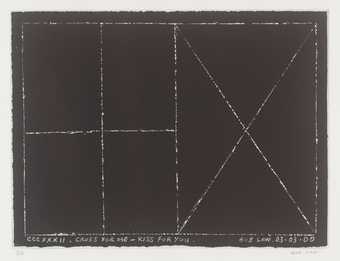

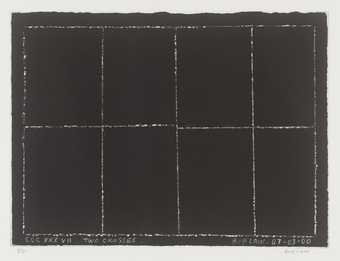

Bob Law Cross for Me - Kiss for You

2000 -

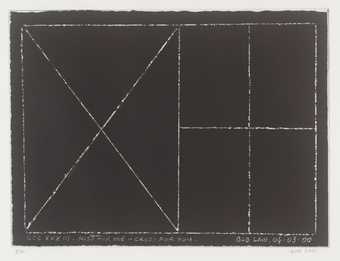

Bob Law Kiss for Me - Cross for You

2000 -

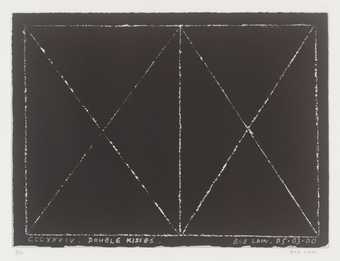

Bob Law Double Kissers

2000 -

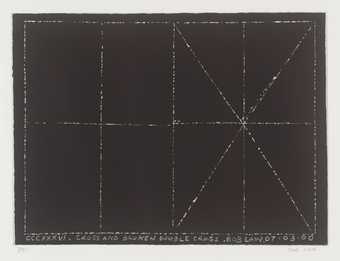

Bob Law Cross & Broken Double Cross

2000 -

Bob Law Two Crosses

2000 -

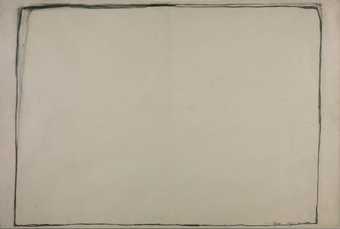

Bob Law Drawing 24.4.60

1960 -

Bob Law Drawing 25.4.60

1960 -

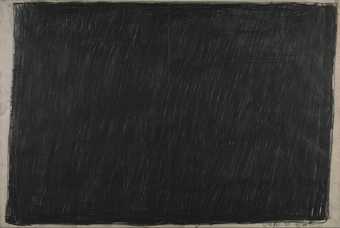

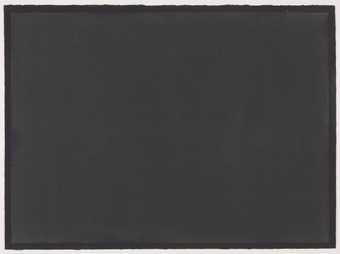

Bob Law No. 62 (Black/Blue/Violet/Blue)

1967 -

Bob Law Untitled 29.8.87

1987 -

Peter Startup Separation

1965 -

Bob Law Nothing to be Afraid Of IV 15.08.1969

1969 -

Bob Law Mr Paranoia VII 20.10.72 (No. 106) 1972

1972 -

Bob Law Twentieth Century Ikon Series 8.8.67

1967 -

Bob Law Tall Obelisk with Two Holes and a Notch

1981 -

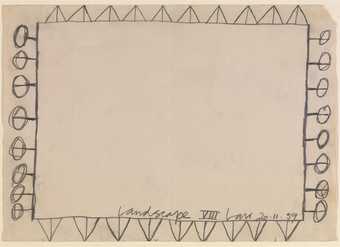

Bob Law Landscape VIII

1959