Sir John Everett Millais, BtOphelia 1851–2Tate

Beauty as Protest 1845–1905

17 rooms in Historic and Early Modern British Art

The men and women of Pre-Raphaelite circle question mainstream Victorian culture and ideas

In 1848, revolutions all over Europe spread the spirit of reform across the continent. Three art students, Dante Gabriel Rossetti, John Everett Millais and William Holman Hunt, launch a revolution in art. Rossetti is the son of an Italian revolutionary. Hunt worked in a textile warehouse for the popular political activist, Richard Cobden. Hunt and Millais watch Chartist campaigners march on parliament to petition for workers’ rights. In November 1848, the trio create a radical artistic group called the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood.

The Pre-Raphaelites reject the academic art of the Royal Academy, which holds certain historical subjects and styles in high esteem. They look for authenticity in art of all periods, but seek relevance to their modern times. The seven members, alongside the men and women in their wider circle, choose subjects that cast a light on social issues. They update stories from the Bible, Shakespeare and medieval poetry. They paint real people, objects and settings. Later on, their art becomes concerned with beauty and imagined worlds.

Sorry, no image available

Walter Crane, author William Morris, Monopoly; or, How Labour is Robbed 1890

1/30

artworks in Beauty as Protest

Sorry, no image available

Jane Morris, Jenny Morris, William Morris, Honeysuckle embroidery 1880

2/30

artworks in Beauty as Protest

Sorry, no image available

William Morris, News from Nowhere 2015

3/30

artworks in Beauty as Protest

Sorry, no image available

Morris & Co. (London, UK), Pipernel design, wallpaper book 1917–1939

4/30

artworks in Beauty as Protest

Sorry, no image available

Thomas Gaskell, Gaskell Wall Clock 1848

5/30

artworks in Beauty as Protest

Sorry, no image available

Walter Crane, author William Morris, Useful Work Versus Useful Toil 1893

6/30

artworks in Beauty as Protest

Sorry, no image available

Rebecca Solomon, A Young Teacher 1861

7/30

artworks in Beauty as Protest

William Holman Hunt, The Awakening Conscience 1853

Hunt’s modern life painting represents a wealthy man visiting his mistress in an apartment which he has provided for her. The tune that he idly plays on the piano has reminded her of her earlier life and she rises from his lap towards the bright outside world (made visible to the viewer in the mirror). The claustrophobic space is filled with intricate clues, such as the bird trying to escape from a cat and the female figure enclosed in a glass dome, which echoes the shape of the painting.

Gallery label, November 2016

8/30

artworks in Beauty as Protest

Thomas Woolner, Puck 1845–7

Puck is a mischievous invisible fairy in Shakespeare’s A Midsummer Night’s Dream. Thomas Woolner has illustrated a scene here from an ‘Imaginary Biography’ of Puck. He alights on a mushroom to save a sleeping frog from a hungry snake. The sculpture captures the instant before a sudden movement – as Puck touches the frog with his foot it will jump away just before the snake attacks.Ideal or poetic subjects drawn from literature, mythology or history, were highly regarded by sculptors in the mid-nineteenth century.

Gallery label, July 2007

9/30

artworks in Beauty as Protest

Martha Darley Mutrie, Wild Flowers at the Corner of a Cornfield c.1855–60

10/30

artworks in Beauty as Protest

William Dyce, Pegwell Bay, Kent - a Recollection of October 5th 1858 ?1858–60

Dyce’s painting was the product of a trip he made in the autumn of 1858 to the popular holiday resort of Pegwell Bay near Ramsgate, on the east coast of Kent. It shows various members of his family gathering shells. The artist’s interest in geology is shown by his careful recording of the flint-encrusted strata and eroded faces of the chalk cliffs. The barely visible trail of Donati’s comet in the sky places the human activities in far broader dimensions of time and space.

Gallery label, November 2016

11/30

artworks in Beauty as Protest

Dante Gabriel Rossetti, Rosa Triplex 1867

triple portrait of Charles I by Van Dyck. Rossetti's

Gallery label, August 2004

12/30

artworks in Beauty as Protest

Ford Madox Brown, Chaucer at the Court of Edward III 1856–68

This picture is a replica of Ford Madox Brown’s largest and most ambitious painting, exhibited in 1851. It was significant for its portrayal of natural sunlight and was his first attempt ‘to carry out the notion ... of treating the light and shade absolutely, as it exists at any one moment, instead of approximately or in generalized style’. This pursuit of ‘truth to nature’ was consistent with Pre-Raphaelite ideals, as was his careful workmanship. The picture’s subject, Geoffrey Chaucer, reflects the growing popularity with artists of English literature instead of more conventional classical myths and biblical tales.

Gallery label, November 2016

13/30

artworks in Beauty as Protest

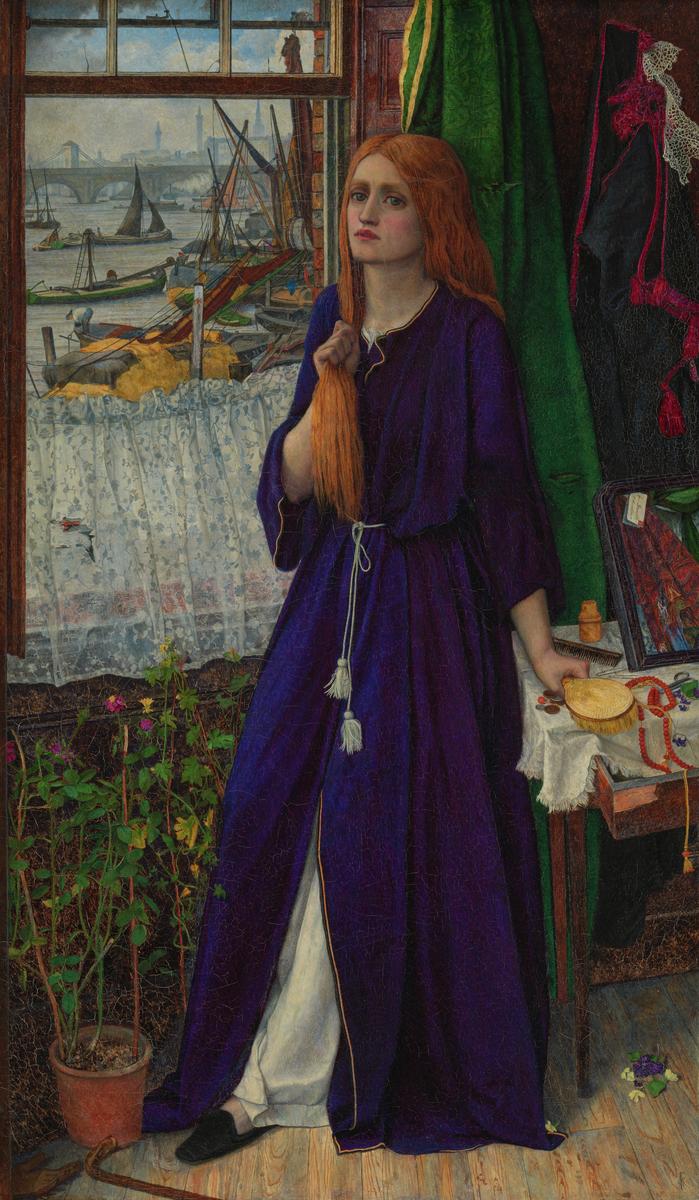

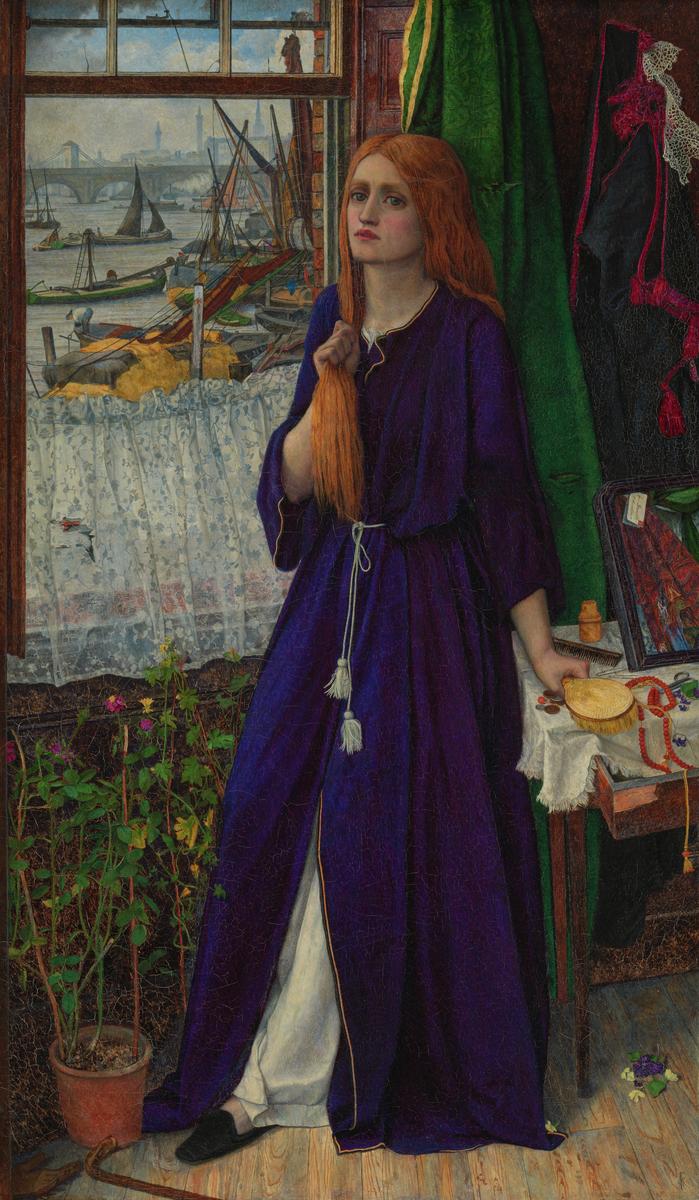

John Roddam Spencer Stanhope, Thoughts of the Past exhibited 1859

This modern-life picture shows a prostitute in her lodgings overlooking the Thames. Her situation is indicated by the shabby interior with jewellery and money strewn across her dressing table, and the man’s glove and walking stick on the floor. Waterloo Bridge and Hungerford Bridge are shown in the distance straddling the busy polluted river. A sickly-looking plant by the woman’s side suggests her impending doom.

Gallery label, November 2016

14/30

artworks in Beauty as Protest

John Brett, Lady with a Dove (Madame Loeser) 1864

Jeannette Loeser, the subject of this portrait, was romantically involved with John Brett until the spring of 1865. The portrait was largely painted in Rome in the early months of 1864, and completed in London in August that year. The wing of the dove echoes the curved outline of the sitter’s skirt, and the dove motif is repeated in the mosaic brooch on her shoulder. Each corner of the frame is decorated with a winged cherub that looks into the picture as if in admiration of her beauty.

Gallery label, November 2016

15/30

artworks in Beauty as Protest

William Holman Hunt, Claudio and Isabella 1850

This scene represents a moment of complex moral dilemma for Claudio and Isabella, characters from Shakespeare’s Measure for Measure. Claudio has been sentenced to death by Angelo, deputy to the duke of Vienna. He can only be saved if his sister, Isabella, sacrifices her virginity to Angelo. Claudio’s awkward pose draws attention to his prison shackles. The apple blossom blown by the wind at his feet symbolises his readiness to buy his own reprieve with Isabella’s chastity. Her white habit emphasises her purity. Holman Hunt summarised the moral of his picture as: ‘Thou shall not do evil that good may come.’

Gallery label, November 2016

16/30

artworks in Beauty as Protest

Joanna Mary Wells, Gretchen 1861

This picture alludes to a central scene in Faust, the tragic play published by German writer Johann Wolfgang von Goethe in the early 19th century. In the play, Gretchen, confused, seduced and pregnant by Faust, seeks solace in church. The sitter for the work was probably Wells’s nursery maid. Women artists had limited access to models at the time. Joanna Wells (née Boyce) had established a reputation during the 1850s as a painter of portraits, genre and landscape. She also wrote art reviews for the Saturday Review. Her career ended prematurely at the age of thirty. Wells herself was pregnant when she began this painting. She died shortly after the birth and the picture was left unfinished.

Gallery label, December 2020

17/30

artworks in Beauty as Protest

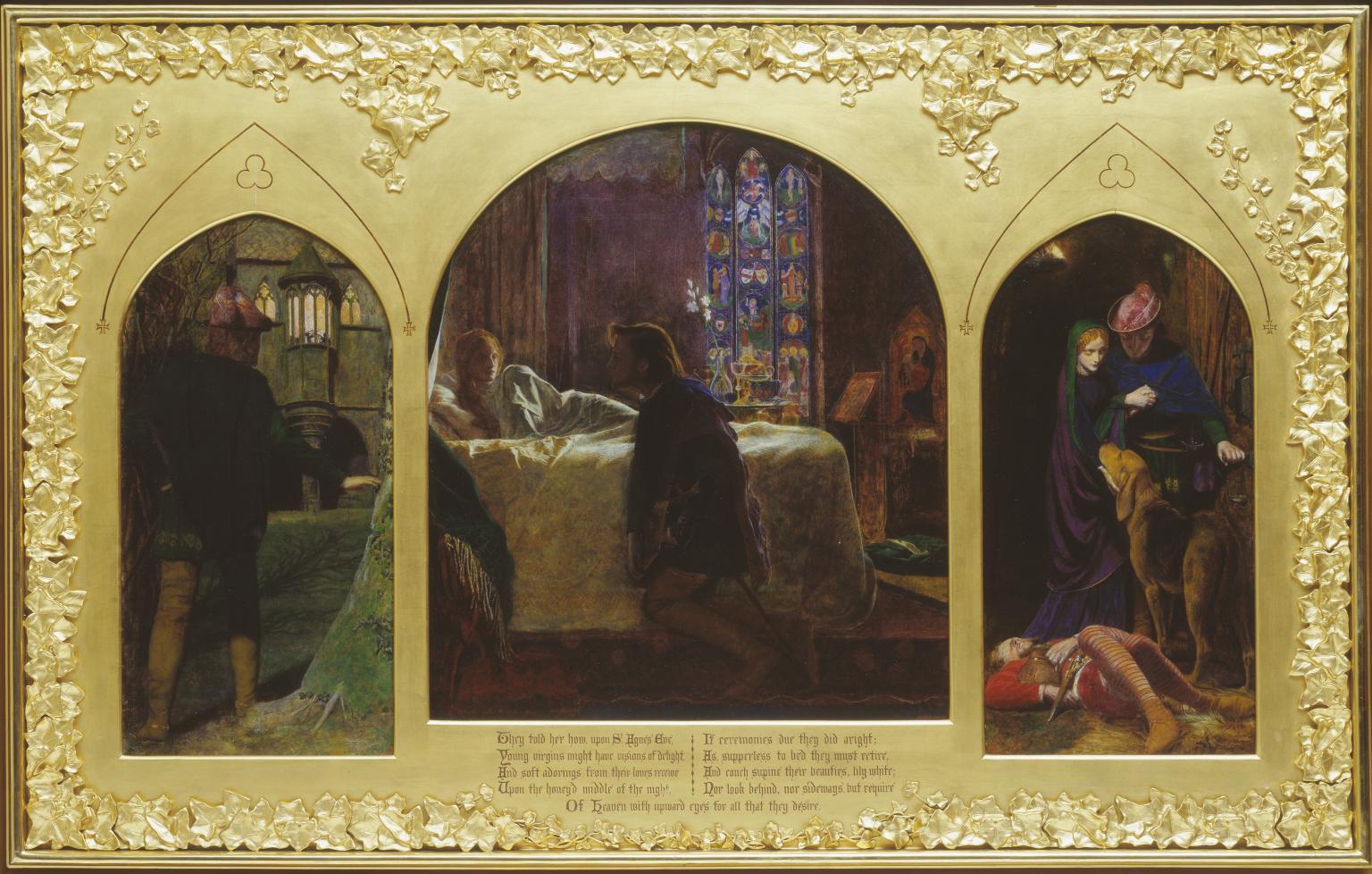

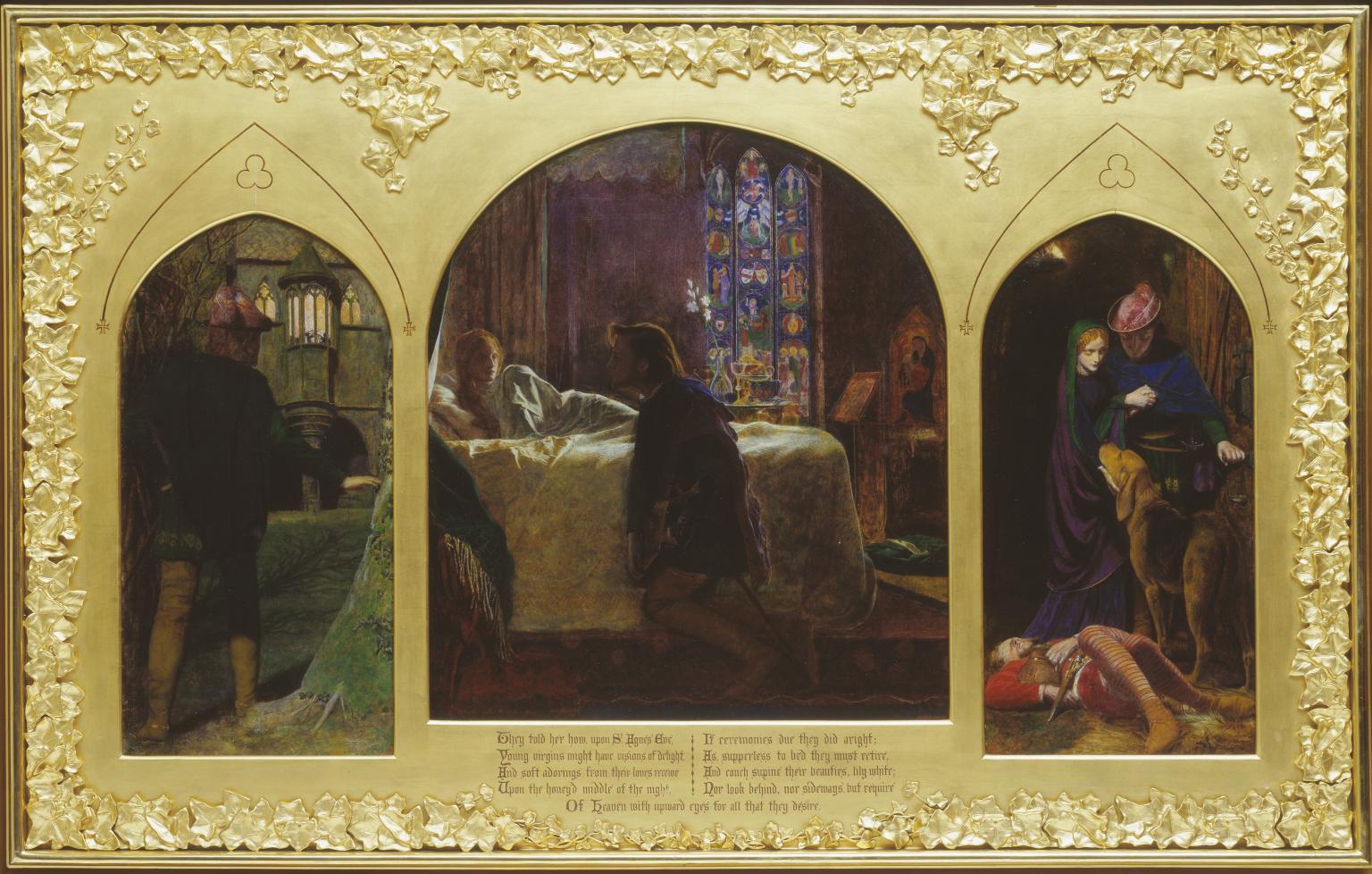

Arthur Hughes, The Eve of St Agnes 1856

This work was based on John Keats's poem The Eve of St Agnes (1820), inspired by the folk belief that a woman can see her future husband in a dream if she performs certain rites the day before the feast of St. Agnes, the patron saint of virgins. The frame is inscribed with the fourth verse of the poem, which sets the scene for the three episodes which Hughes depicts. First, Porphyro defies Madeleine’s family to approach the castle, where a banquet is in progress. He then awakens Madeline from her dreams. Finally, the lovers silently escape from the dark castle into the night.

Gallery label, March 2022

18/30

artworks in Beauty as Protest

Frederic George Stephens, Mother and Child c.1854

Stephens painted this in the first year of the Crimean War (1853-6) and the major world event plays out in the setting of a Victorian nursery. The child pauses playing to reach towards his mother as she reacts to a letter which brings bad news from the conflict. Stephens encloses the figures in a curved frame like a traditional Madonna and Child and employs everyday objects, such as the military toys, as symbols. Stephen’s extremely detailed Pre-Raphaelite style was time-consuming and the picture was never finished.

Gallery label, August 2018

19/30

artworks in Beauty as Protest

Henry Wallis, Chatterton 1856

This highly romanticised picture created a sensation when it was first exhibited at the Royal Academy in 1856. Thomas Chatterton was a poet whose ‘gothic’ writings, melancholy life and youthful suicide fascinated artists and writers of the 19th century. At an early age, he wrote fake medieval histories and poems, which he copied onto old parchment and passed off as manuscripts from the Middle Ages. The fraud was later discovered. In London he struggled to earn a living writing tales and songs for popular publications. Penniless, he took his own life by swallowing arsenic at the age of 17.

Gallery label, November 2016

20/30

artworks in Beauty as Protest

Dante Gabriel Rossetti, Sancta Lilias 1874

This is the abandoned first version of one of Rossetti’s most important pictures, The Blessed Damozel (1875–8). He first treated the subject in a poem which, inspired by Dante’s love for Beatrice, describes a dead woman’s yearning for her still-living lover. In the completed painting, Rossetti shows the Damozel looking down on her beloved from Heaven; this is the scene shown here. Rossetti’s fascination with the separation imposed by death proved eerily prophetic when his wife Elizabeth Siddall died of an overdose of laudanum in 1862.

Gallery label, November 2016

21/30

artworks in Beauty as Protest

Ford Madox Brown, Carrying Corn 1854–5

This intensely coloured painting captures a harvest field just before sunset. Each landscape element is faithfully recorded in jewel-like colours. This is a nostalgic view of rural England, untouched by industrialisation and modern city life. Ford Madox Brown’s view is typical of idealists of the time who believed that an engagement with nature offered spiritual redemption from urban corruption. Brown and his family were facing financial hardship at the time this picture was painted. It was one of a number of ‘potboilers’, modest and straightforward landscapes he hoped would sell easily.

Gallery label, July 2007

22/30

artworks in Beauty as Protest

Sir Edward Coley Burne-Jones, Bt, Frieze of Eight Women Gathering Apples 1876

The theme of this panel would appear to be connected with the legend of the Garden of the Hesperides, a subject Burne-Jones treated on several other occasions. It may have been intended as an overmantel for a fireplace or as a decorative panel for a cassone or chest. The gold relief reflects the artist’s interest in early Renaissance art where such decoration was used extensively. The frieze may have been commissioned by the artist’s patron, the MP and collector William Graham, whose daughter Lady Horner owned a similar panel.

Gallery label, November 2016

23/30

artworks in Beauty as Protest

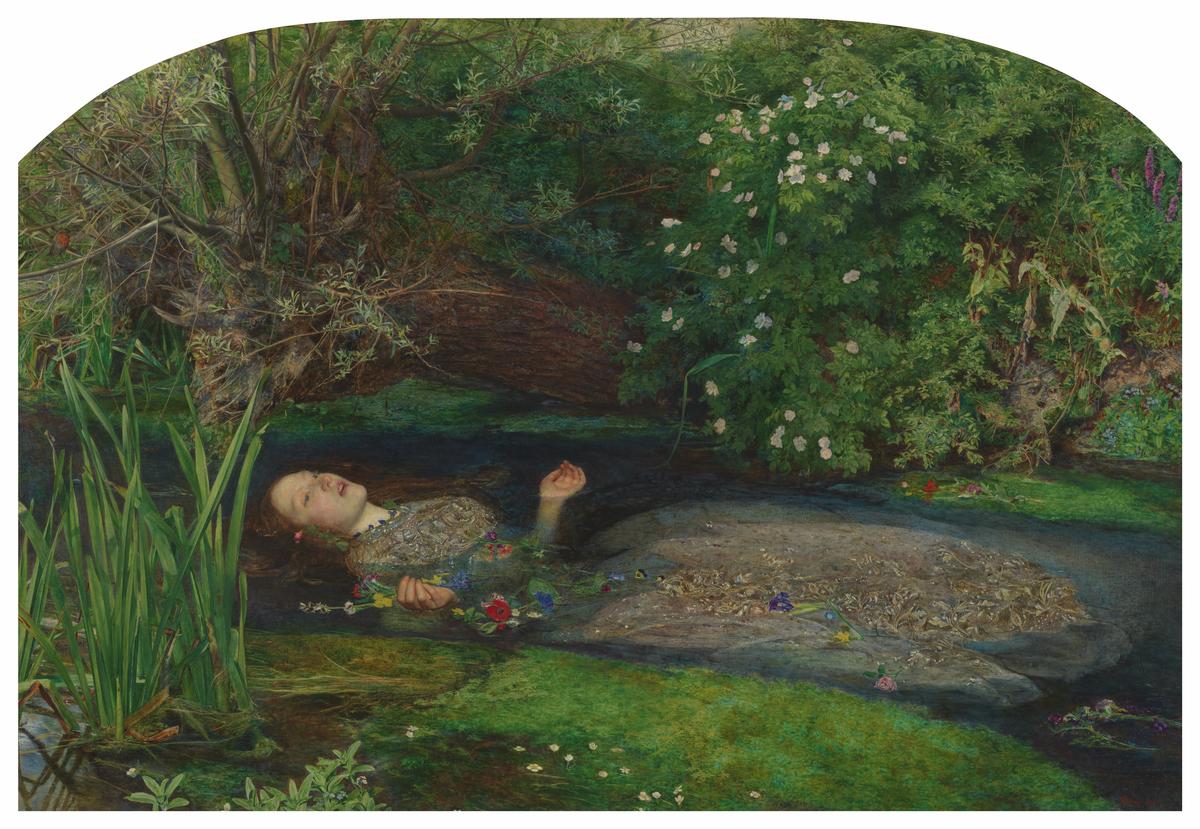

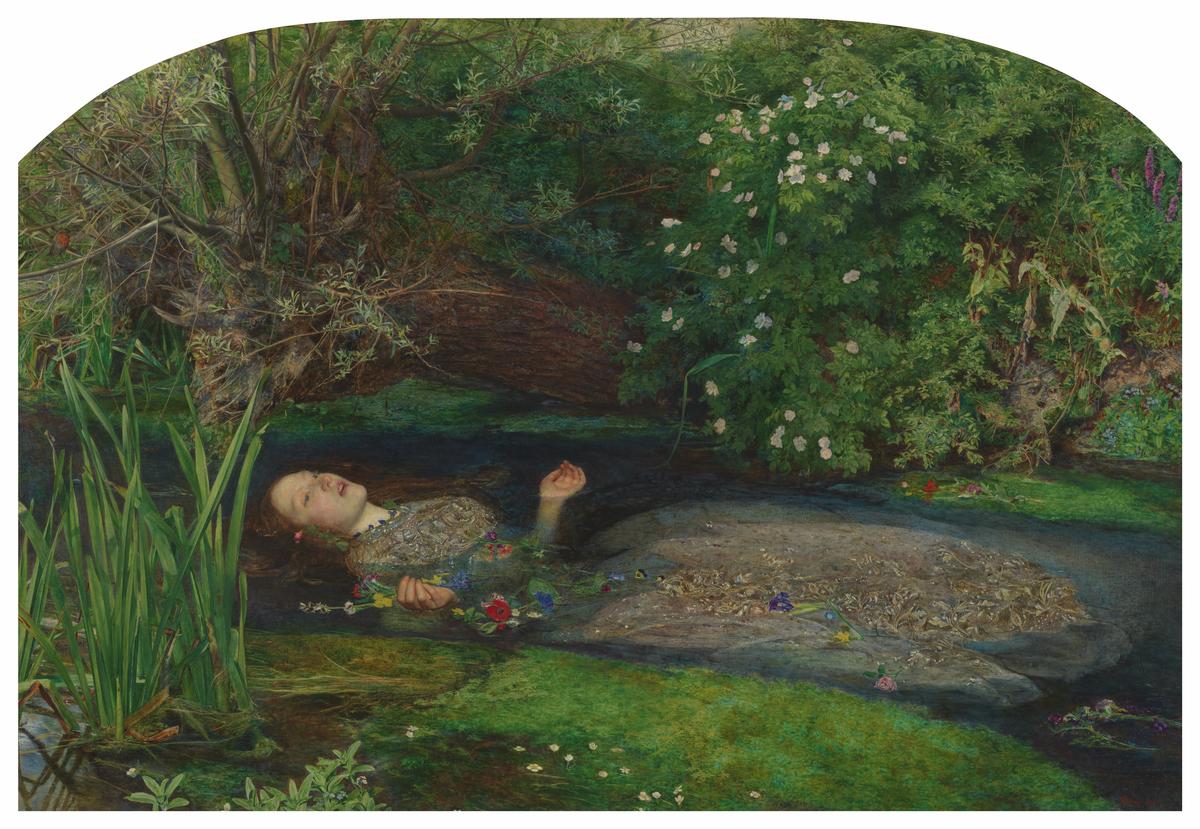

Sir John Everett Millais, Bt, Ophelia 1851–2

This work shows the death of Ophelia, a scene from Shakespeare’s play Hamlet. Traumatised when Hamlet breaks off their betrothal and accidentally kills her father, she allows herself to fall into a stream and drown. The flowers she has been collecting symbolise her story, the poppies representing death. Millais painted the lonely setting leaf-by-leaf over many months by the Hogsmill River, Surrey. Afterwards, the artist, poet and model Elizabeth Siddall posed in a wedding dress in a bath of water at Millais's studio. Through the painting, Millais critiqued the Victorian practice of occasionally arranging marriages for money and status.

Gallery label, March 2022

24/30

artworks in Beauty as Protest

Eleanor Fortescue-Brickdale, The Châtelaine exhibited 1904

25/30

artworks in Beauty as Protest

Ford Madox Brown, Our Lady of Good Children 1847–61

26/30

artworks in Beauty as Protest

Ford Madox Brown, The Hayfield 1855–6

Brown painted this landscape directly from nature. The setting is the Tenterden estate at Hendon, north London, looking east at twilight. He finished the final details in his studio, adding a self-portrait in the lower left corner. The effect he sought to capture was the way in which the brown hay was made to appear almost pink by contrast with the dense green grass. After it was finished his dealer rejected it on the grounds that he had never seen hay of this colour. Brown later retouched the painting before selling it to his friend and fellow artist William Morris.

Gallery label, November 2016

27/30

artworks in Beauty as Protest

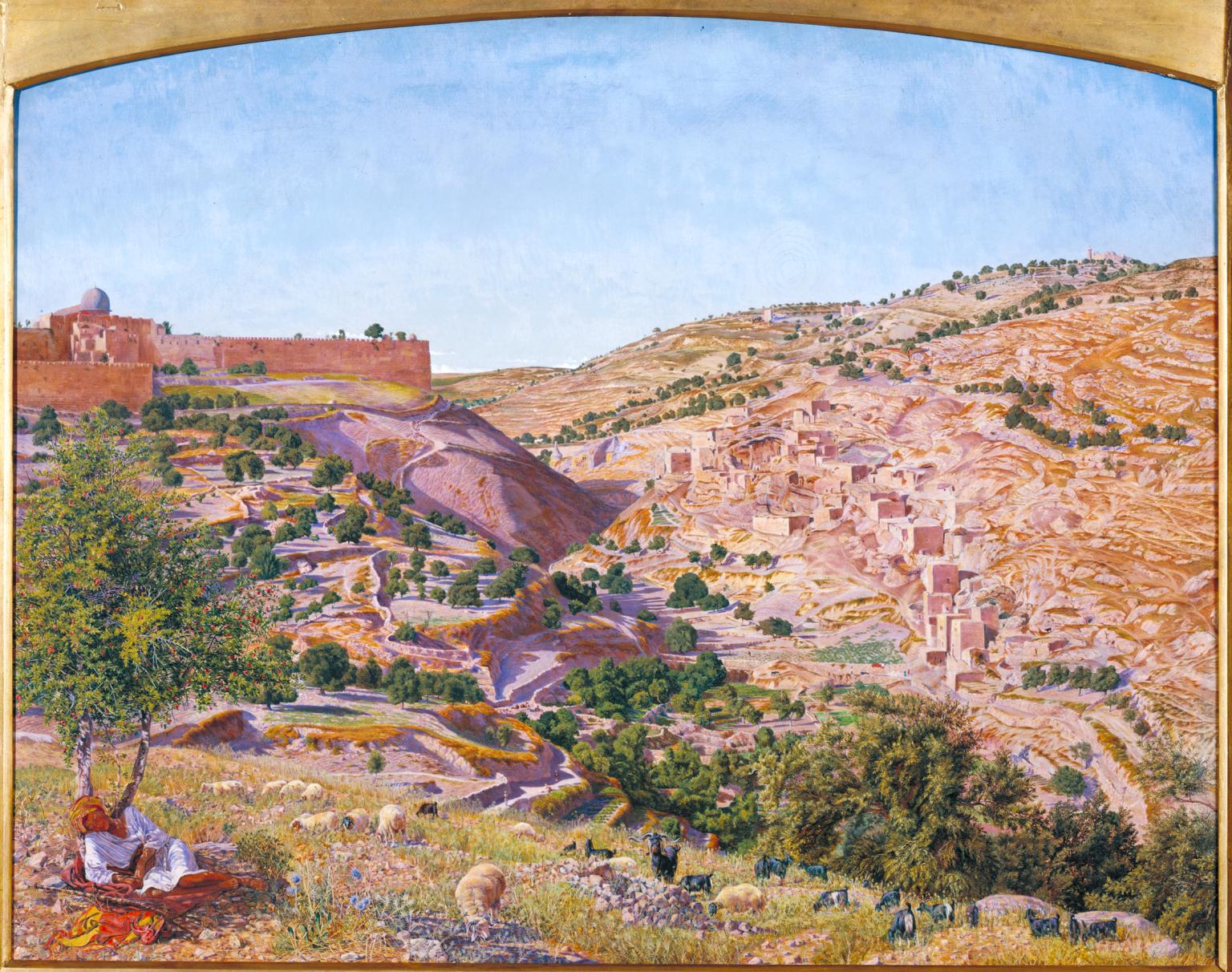

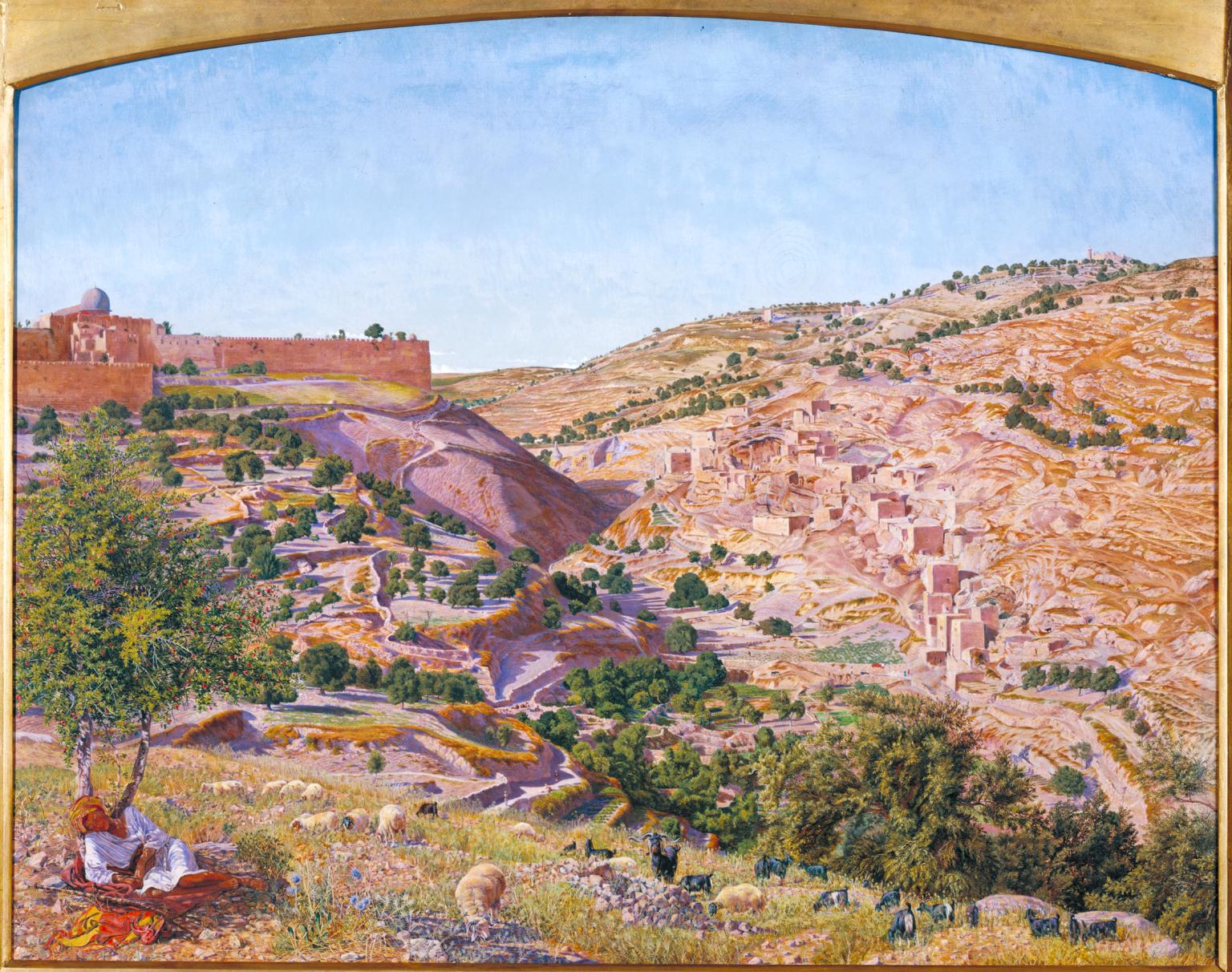

Thomas Seddon, Jerusalem and the Valley of Jehoshaphat from the Hill of Evil Counsel 1854–5

Seddon and his friend Holman Hunt journeyed to the Holy Land in 1854, to bring greater authenticity, spiritual and topographical, to their religious works. This view, painted south of Jerusalem, shows the Mount of Olives and the Garden of Gethsemane, the site of Christ’s anguish before the Crucifixion. The valley of Jehoshaphat was also believed to be where the Last Judgement would take place. Unlike John Martin’s apocalyptic visions, displayed nearby, Seddon represents the site in painstaking, sun-lit detail, paralleling the art critic John Ruskin’s remarks that ‘in following the steps of nature’, artists were ‘tracing the finger of God.’

Gallery label, March 2010

28/30

artworks in Beauty as Protest

Henry Alexander Bowler, The Doubt: ‘Can these Dry Bones Live?’ exhibited 1855

This young woman, leaning on the gravestone of a man called John Faithful, is contemplating religious doubt. In particular, the Christian belief that the dead will be resurrected on the Day of Judgement. Long-standing religious beliefs were being disrupted at the time this was painted. New scientific publications explored theories of evolution, challenging literal readings of the Bible. Her question appears to be answered by the growing chestnut tree and the stone at its base, carved with the word Resurgam’, which translates as ‘I shall rise again’. The blue butterfly on the skull symbolizes the human spirit.

Gallery label, August 2018

29/30

artworks in Beauty as Protest

Sir John Everett Millais, Bt, Christ in the House of His Parents (‘The Carpenter’s Shop’) 1849–50

This picture was exhibited with words from the Old Testament, often seen as prefiguring Christ’s Crucifixion: ‘And one shall say unto him, What are these wounds in thine hands? Then shall he answer. Those with which I was wounded in the house of my friends.’ Millais based the setting on a real carpenter’s shop. Symbols of the Crucifixion figure prominently: the wood, the nails, the cut in Christ’s hand and the blood on his foot. Millais was viciously attacked in the press for showing the holy family as ‘ordinary’. Charles Dickens described Christ as ‘a hideous, wry-necked, blubbering, red-haired boy in a night-gown.’

Gallery label, November 2016

30/30

artworks in Beauty as Protest

Art in this room

Sorry, no image available

Sorry, no image available

Sorry, no image available

Sorry, no image available

Sorry, no image available

Sorry, no image available

Sorry, no image available

You've viewed 6/30 artworks

You've viewed 30/30 artworks